They were your most dependable person.

– Always delivered.

– Rarely complained.

– Knew the work inside out.

So, when the opportunity came up, the decision felt obvious.

You promoted them.

And for a while, everything looked fine.

Then the cracks began to show.

– The team became hesitant.

– Decisions slowed down.

– The new manager looked stressed, impatient, and constantly overwhelmed.

What happened?

Nothing went wrong. But something important was never addressed.

The promotion mistake organizations rarely question. Most organizations promote people for being excellent individual contributors. But the role they step into is no longer about individual performance.

It’s about:

- Enabling others to perform

- Letting go of control

- Making space for different styles

- Leading through influence, not expertise

That shift is enormous. Yet we rarely acknowledge it.

Instead, we assume that a high performer will naturally become a good manager. That assumption is where many leadership journeys quietly derail.

Why high performers struggle when they become managers:

1. The identity shift is underestimated

As an individual contributor, success is personal.

- I deliver.

- I solve.

- I get results.

As a manager, success becomes indirect.

- My team delivers.

- I support, coach, and enable.

- Results are shared.

For high performers, this feels like losing control and sometimes, losing relevance. No one prepares them for that emotional shift.

2. Letting go feels risky

High performers often have high standards. They know what “good” looks like because they’ve lived it. So, when team members work differently, slower, or make mistakes, the instinct is to step in.

Not out of ego but out of fear.

Fear that:

- Quality will drop

- Deadlines will slip

- They will be held responsible

Micromanagement isn’t a leadership flaw. It’s usually a trust gap created by pressure.

3. People leadership is never actually taught

Many first-time managers are given:

- Targets

- Teams

- Responsibilities

But very little guidance on:

- Giving feedback

- Handling conflict

- Managing emotions (theirs and others)

- Balancing empathy with accountability

They are expected to “figure it out.”

And when they struggle, the label quickly changes from top performer to poor manager.

The cost organizations don’t immediately see:

When high performers struggle as managers, the impact goes beyond one role.

– Teams become disengaged.

– Good employees leave.

– Managers burn out silently.

Over time, the leadership pipeline weakens.

Ironically, the organization loses the very talent it worked hard to grow—either through attrition or disengagement. And this pattern repeats itself with the next promotion.

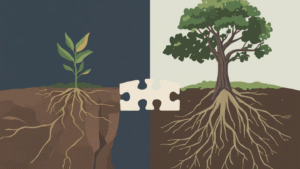

What actually helps the transition:

The shift from performer to manager doesn’t need a dramatic intervention. It needs early, intentional support.

What makes a difference:

- Preparing people before the promotion

- Setting clear expectations of what leadership looks like

- Coaching during the first 90 days

- Normalizing uncertainty instead of hiding it

Most importantly, it requires acknowledging this truth:

Leadership is not a reward. It is a responsibility that needs preparation.

When organizations treat leadership transitions as learning journeys, not trial-by-fire moments, both managers and teams stabilize faster.

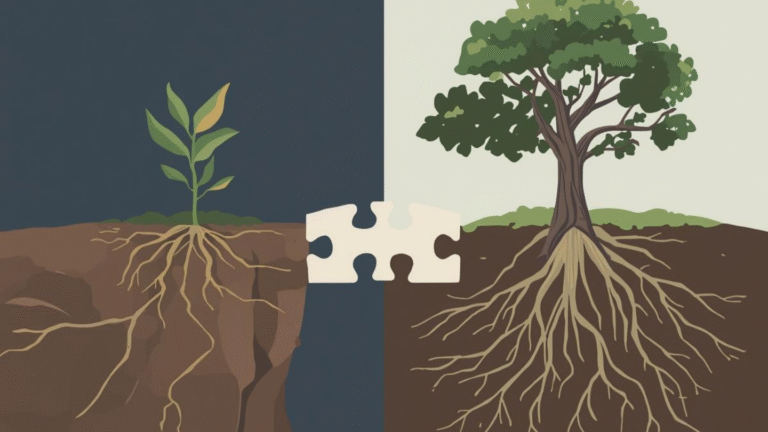

A reality many organizations recognize too late:

We have seen strong performers regain confidence as managers, not because they changed overnight, but because the organization changed its approach.

They were supported instead of judged. Guided instead of monitored. Given space to learn instead of pressure to “already know.”

The result wasn’t perfection. It was progress. And progress is how leadership is built.

A question worth reflecting on:

Before the next promotion, it’s worth asking-

Are we promoting people into leadership or into struggle?

The answer often determines the future of your leadership bench.

Promoting high performers shouldn’t mean leaving them to struggle alone. Leadership transitions succeed when support begins before the promotion.